Pan Pantziarka (PP), the co-founder and Chairman of the Trust is also a scientist involved in research on the use of non-cancer drugs as new agents in cancer (a process known as drug repurposing). He has also published research on the causes of cancer in people with LFS, and proposed a theory that suggests that we may be able to reduce the cancer risk in LFS using existing and safe drugs, such as metformin and aspirin. This research has been supported by the Trust. He is interviewed here by Jennifer Mallory (JM), from Living LFS.

JM: In your recent publication, you present a hypothesis that people with LFS are “primed for cancer”. Can you explain what this means?

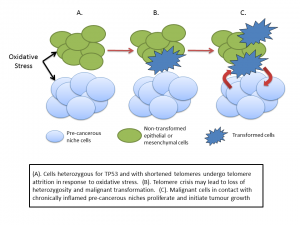

PP: The basic idea is that to date most of the attention on TP53 and LFS has been on the tumour suppressor activity – the traditional ‘guardian of the genome’ view. But we are increasingly learning that TP53 regulates a broad range of biological activities over and above the tumour suppressor side of things. For example p53 signalling is involved in responses to metabolic stress, in inflammation, aging and immune function. I think these things are also important to the LFS story. When we look at these TP53 functions too we get a more nuanced view of cancer development. It suggests that many of the support systems that cancer needs in order to take off are already there in people with a mutated TP53 gene.

JM: You discuss a “precancerous niche”, can you help us understand what this is and how does it relate to another term we hear lately – microenvironment?

PP: The microenvironment describes the tissues and cells which surround a tumour. Cancer is not just a disease of tumour cells – it’s a disease that includes a set of support systems that helps the tumour thrive and spread. A tumour needs a blood supply to provide nutrients and oxygen, it needs to subvert the immune system and so on. All cancers depend on a supporting microenvironment – think of a tumour as a complex ecosystem of different cells in addition to the cancer cells. In the case of the pre-cancerous niche I suggest that many elements of the microenvironment are in place before the appearance of the tumour itself. And that this pre-cancerous niche arises because of the mutated TP53 gene.

JM: Can you explain the importance of precancerous niches to people with LFS in relation to cancer risk and prevention?

PP: Put simply without the supportive microenvironment it’s not possible for tumours to survive and thrive. Now the good news is that where p53 is hard to target directly with drugs, the same is not true of many of the elements of the precancerous niche. We can tackle chronic inflammation, some aspects of immune dysfunction, metabolic stress and so on. If we can reduce the incidence of precancerous niches then we can potentially reduce the incidence of cancer in people with LFS – if my theory is correct, of course.

JM: Will addressing the “priming of the soil” so to speak in LFS patients, (diet, supplements) help with not only prevention, but could it help with how effective existing treatments are?

PP: There is currently a huge interest in medicine in looking at how aspects of the microenvironment impact on cancer treatment and resistance. This applies to all cancers, not just those associated with LFS. Much of the work I am doing as part of the Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO) project is about identifying existing non-toxic, non-cancer drugs which have some influence on the microenvironment and which might be added to existing therapies. If we can reverse drug resistance, immune tolerance, chronic inflammation and so on then we’ve got a better chance of improving overall survival.

JM: Would you recommend adding a complete integrative medical workup including inflammation, oxidative stress, and telomere testing to annual screening to help adjust lifestyle, diet and exercise?

PP: I would love for this to happen. It’s frustrating that there’s so much we don’t know about people with LFS. Why is it that some people with the mutated gene don’t develop cancers and others do? It’s not even as if some of these tests are difficult or expensive. If we could track something simple like the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio over time, would that signal the conditions that lead to cancer development? Similarly for telomere attrition, how does this compare between affected and non-affected family members and does it change over time? And, by tracking them, perhaps we can start to see which diet, lifestyle or drug interventions have positive benefits in reducing chronic inflammation and so on.

JM: One of the limits to research for LFS is how rare it is, there just aren’t enough people to generate sufficient data for clinical trials. You have a great suggestion that could really help advance research for LFS as well as other rare hereditary cancer syndromes- can you tell us more about this?

PP: The precancerous niche idea is all about the phenotype not the genotype – in other words it’s about the physical effects of chronic inflammation, angiogenesis and so on rather than the specific genetic drivers. There are many drivers of these things, not just mutated TP53. We already know that around 30% of LFS affected individuals don’t have the TP53 mutation, but they still have the elevated cancer risk. I suggest that this is because they also develop precancerous niches very easily. Taking this a step further we can speculate that other cancer predisposition syndromes feature the same precancerous niches but driven by different gene mutations. If this is the case then we can look at interventions that tackle these niches in a much bigger population than LFS – potentially opening the way to clinical trials that have enough people in them to show one way or another whether we can actively reduce cancer risk.

JM: What is one thing you would like the LFS community to take away from this article?

PP: I think the key idea is that our genes are not our destiny. That there may be active interventions – be it drugs, exercise, diet or all three – that can reduce the risk of cancer incidence. There’s a lot of good LFS research out there, but we need to move the agenda from looking at genes or at new scanning protocols to looking for risk reduction strategies.

JM: This research was supported by the George Pantziarka TP53 Trust, are there plans for follow up with some of the promising avenues presented?

PP: When we started the Trust we wanted to support more research in LFS – though to be honest I never imagined that I would be carrying out some of that research myself. But I’ve started a line of thought that I think warrants continued investigation – by myself and by others. It would be great to have some new data to show whether my theories are right or wrong. I think also the idea of extending this to other cancer predisposition syndromes is definitely worth exploring given it opens a door to new clinical trials. However all of this needs funding and there’s a limit to how much of the Trust’s funding can go into this. We have a lot of other ideas we want to explore, including starting a TP53 Registry and organising the first UK LFS meeting. So, if anyone knows of a funding source interested in LFS research then please let me know!