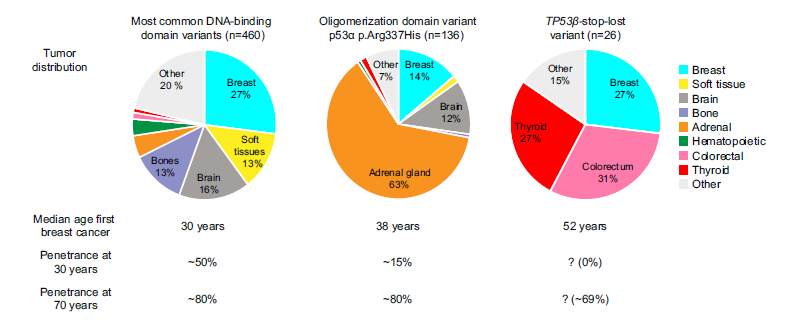

The first piece of research that we funded was back in 2017, when we funded work in Dr Jean-Christophe Bourdon’s p53 lab at Dundee University. This work evolved to explore the activity of what are called p53 isoforms (see here and here for details). Part of that work ended up looking at a set of four Dutch families who had histories of repeated cancers but did not match any of the cancer-predispositions like LFS, Lynch Syndrome or others. The pattern of cancer in these families showed that there was an inherited mutation somewhere, the behaviour was very much like LFS in that it was passed down through generations of these families. On the other hand the pattern of cancer was also different from LFS – cancers occurred at older ages and there were none of the brain, sarcomas and other cancers that are common in LFS, as shown below.

This is where the p53 isoforms come in. When a person is tested for LFS their TP53 gene is sequenced and the core part of it checked for what is called a ‘pathogenic variant’ (which we used to call a mutation). In the case of these families the results came back showing no problem. However, by looking outside of this core part of the gene the researchers – from the Netherlands, UK and Croatia – discovered a new type of variation that affected some of the p53 isoforms and not the main p53 protein. What’s more, they showed that this isoform could affect the main protein, hence increasing the cancer risk. In other words, despite not fitting in with the traditional definitions of LFS, these families were in fact carrying a p53 variation that would not be picked up by the standard TP53 tests.

The implication of all this, aside from providing answers to why these four families have this elevated cancer risk, is that even for families where TP53 mutations are not commonly detected, there may in fact be an underlying problem with the TP53 gene. In the past such families were described as having Li-Fraumeni-like Syndrome, or these days they are sometimes referred to as a having ‘phenotypic’ LFS. They are treated as though they have LFS – for example they should get annual whole-body MRI – but are often excluded from study because there is no detected gene mutation. This work suggests that perhaps if TP53 sequencing looked further there might be a driver mutation there after all.

The full paper is available for download here – but be warned, it is highly technical!

Leave a Reply