The MILI trial is designed to test whether metformin, a drug that treats type II diabetes, can reduce the risk of cancer in people with Li Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS). The truth is that we don’t know if it will or not. There’s some preliminary biological evidence to suggest that it will, but in medicine it’s not uncommon that an idea supported by preliminary evidence turns out to not work in practice. The fact is that a very large proportion of clinical trials fail – even when those trials are based on what looks like solid evidence. That’s the whole point of running trials – to put good ideas to hard tests to see if those ideas are effective in people or not.

What is randomisation?

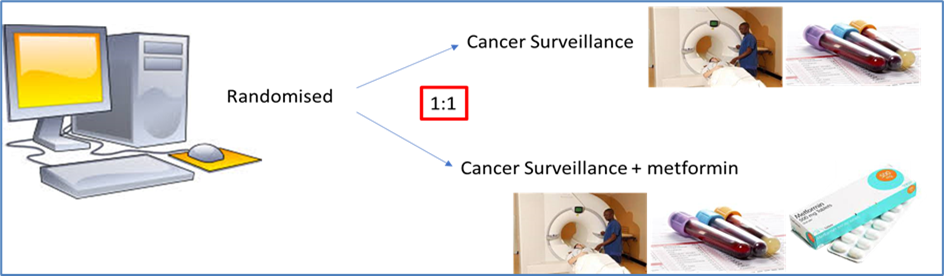

Randomisation is the process of randomly picking people who join a trial to one group or another. Sometimes one group of participants get a new drug and the other group get the existing treatment. Sometimes it’s a new drug versus a dummy drug (called a placebo drug). In some trials there may be more groups – for example there may be two different new drugs and an old drug, or one new drug but at two different doses. In MILI the selection is metformin and surveillance in one group and surveillance in the other group. The question is why?

The aim of randomisation is help us to be sure that a drug works. If we give everyone metformin how would we know whether it works or not? The only way to see if it has an effect is to compare it to something else. If we have two groups of people with LFS that are matched evenly – similar numbers of men and women, and age, in each group – then we have some way of doing a comparison. If at the end of the trial there is no difference in cancer incidence between the metformin group and the no metformin group then it’s going to be hard to say that metformin reduces the risk. On the other hand, if there are fewer people who get cancer in the metformin group then we can say that there is a benefit. Once we know the answer we can get metformin approved so that everybody with LFS gets it on prescription, or if it doesn’t work we can move on to looking at another drug that might be better.

This means that the only way that MILI can succeed is if we can recruit equal numbers in the metformin and no metformin groups. Without that MILI cannot succeed. It’s that simple.

Benefitting in the no metformin group

What if you join MILI and you get assigned to the no metformin group? What’s in it for you personally to stay on the trial? You might think that although there’s a benefit to the LFS community as a whole because we can find out whether metformin works or not, there’s no direct benefit to you in being on the trial. But the fact is that being on a trial is always a benefit to participants, even if they don’t get the new drug or they get a dummy pill in placebo-controlled trials. The benefit is that people on trials usually do better than people not on trials, even when they are on a no treatment arm of a trial. This is because being in a trial means you get a higher standard of care, even if the arm you are on is described as ‘standard care’. You’ll get closer surveillance, more follow-up, greater access to doctors and trial nurses.

This means that if you are asked to join MILI and you get assigned to the surveillance only group you are still going to benefit personally. You won’t get metformin, but you’ll get regular whole-body MRI, blood tests, appointments etc. Even if metformin is not as successful as we hope, you will have benefitted from taking part in the trial.

Longer term

And as a bonus, the blood samples that will be collected from you (whether you are in the metformin arm of the study or not) will be used to understand how and why cancer starts in people with LFS. This is information that, in the long run, may benefit you and your family as it could lead to better treatments in the future. So, by participating in MILI you would have helped to answer a question of huge importance for people with LFS everywhere.

Leave a Reply